Formula 1

The pinnacle of motorsport engineering and driver skill.

Friction

The force that opposes motion between two surfaces. This is what allows tyres to grip the road and allows braking, acceleration, and cornering. However, straight-line friction slows a car down as it is opposing motion rather than being used to change the direction.

Drag

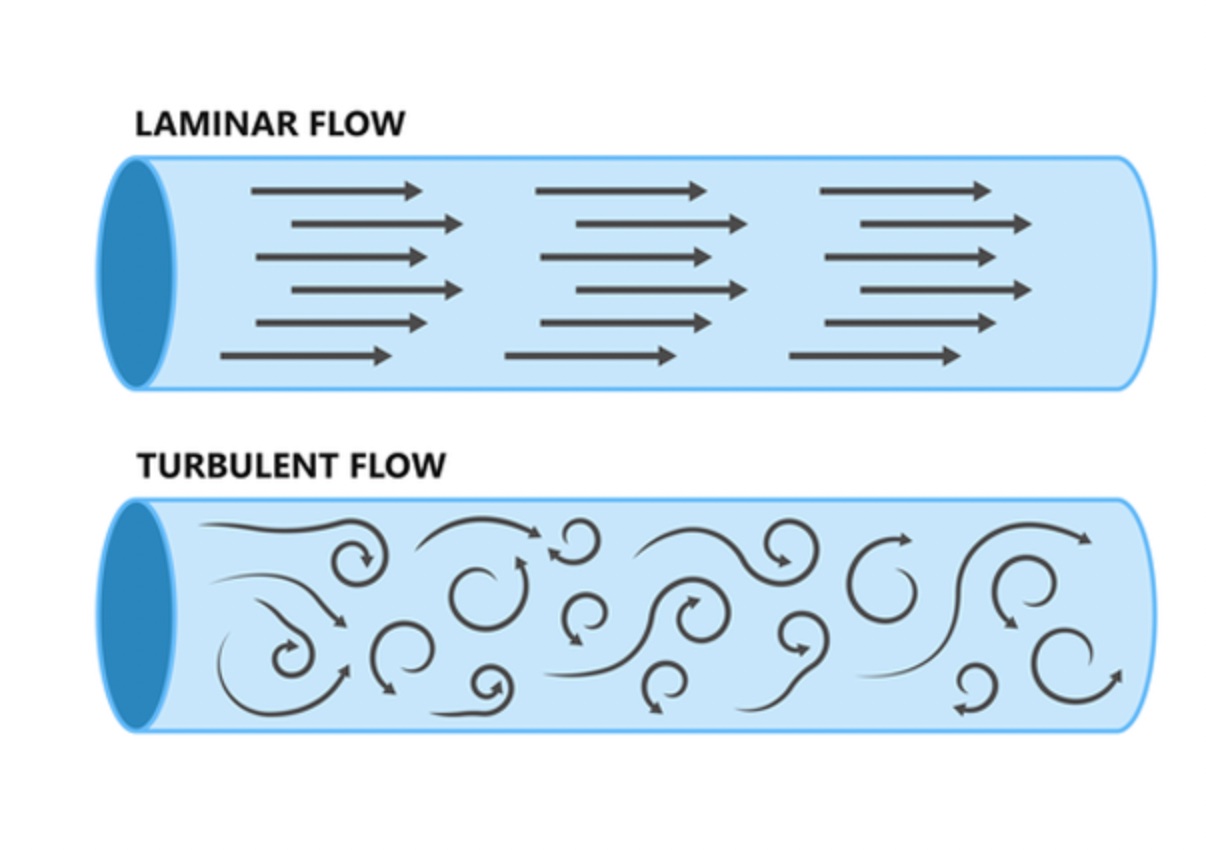

The overall force that opposes motion through a fluid (for F1, this is air). More turbulent (messy) air causes more drag than clean or laminar (uniform) flow of air.

Image taken from: toptec.pk/air-flow-laminar-or-turbulent

Image taken from: toptec.pk/air-flow-laminar-or-turbulent

Downforce

The overall force applied downwards on the car due to airflow over and under the car. This is the same concept as lift on a plane but in the opposite direction.

Inertia

The tendency of an object to resist changes in motion. An F1 car travelling straight wants to keep going straight. In cornering, inertia wants the car to continue straight while the tyres must generate forces to change its direction. This is the same as when you turn in a road car too fast — your body leans the opposite way to the direction you are turning.

Momentum

\[ p = m \times v \]Heavier objects or faster objects have a larger momentum (shown by the equation where momentum is the product of mass and velocity), which means a larger force is required to change direction. F1 cars must balance speed (and therefore high momentum) with the ability for the tyres to generate enough force to corner.

Oversteer and Understeer

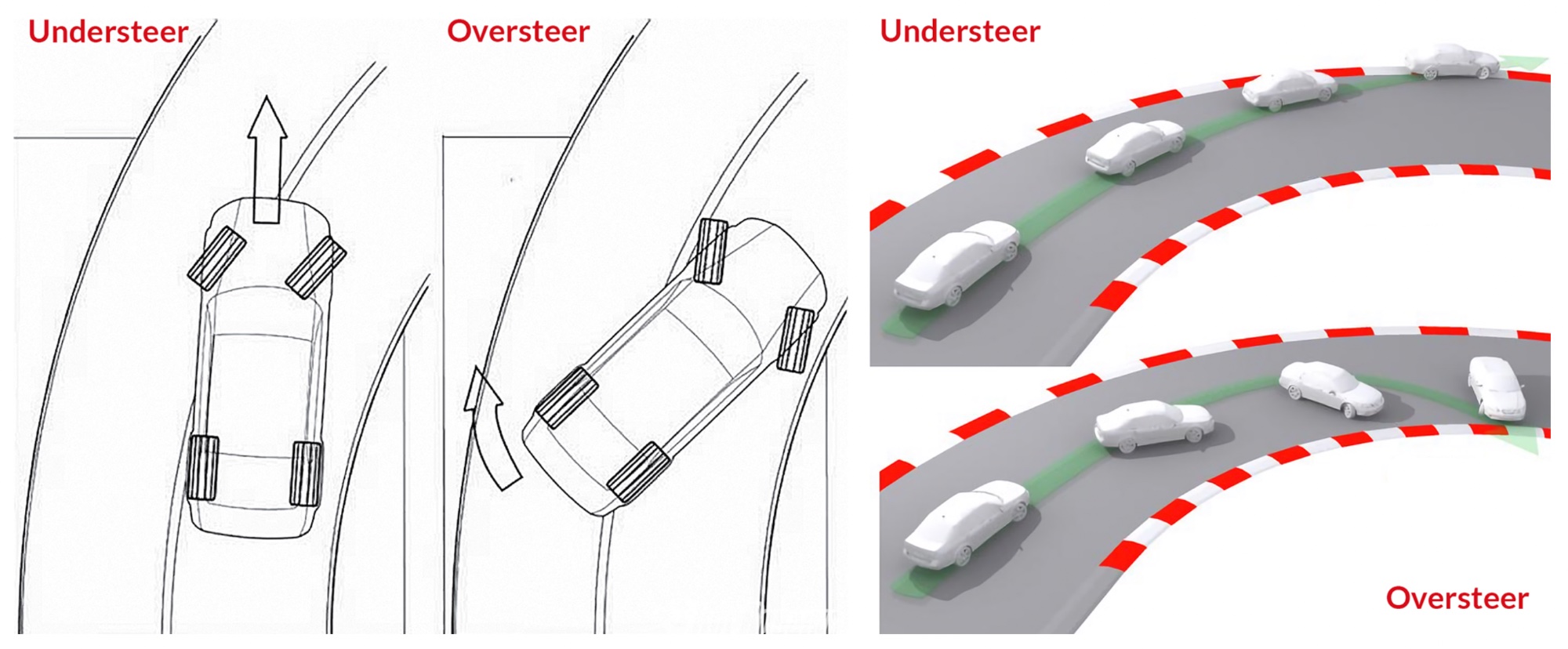

Understeer: The front tyres lose grip before the rears. The car turns less than the steering input — the front end doesn't have enough friction to overcome the car's inertia and loses grip. Oversteer: The rear tyres lose grip before the fronts. The car turns more than the steering input — the rear slides out. The rear doesn't have enough friction to resist rotation. (Drifting is controlled oversteer.)

Image taken from: toc.edu.my — Understeer vs Oversteer

Image taken from: toc.edu.my — Understeer vs Oversteer

History of Formula 1

Drag or scroll to explore key moments

GROOVED TYRES ERA

Why grooves mattered when mechanical grip was sufficient for cornering speeds.

REAR-ENGINE REVOLUTION

How weight distribution and traction reshaped cornering and stability.

SLICK TYRES BECOME STANDARD

Static vs kinetic friction, and how slicks unlocked molecular adhesion.

ANTI-ACKERMANN STEERING ADOPTED

Slip angle dominance flips classic steering geometry on its head.

GROOVED TYRES MANDATED

A safety-driven grip reduction by cutting contact area.

SLICKS RETURN

Slicks compensate for reduced aero; grooves remain essential in the wet.

Performance, Visualised

Rotate a simplified aero model and swap liveries — a clean way to “feel” how packaging and surfaces affect flow.